Death and Life

The ordinary and the extraordinary in the practice of karate

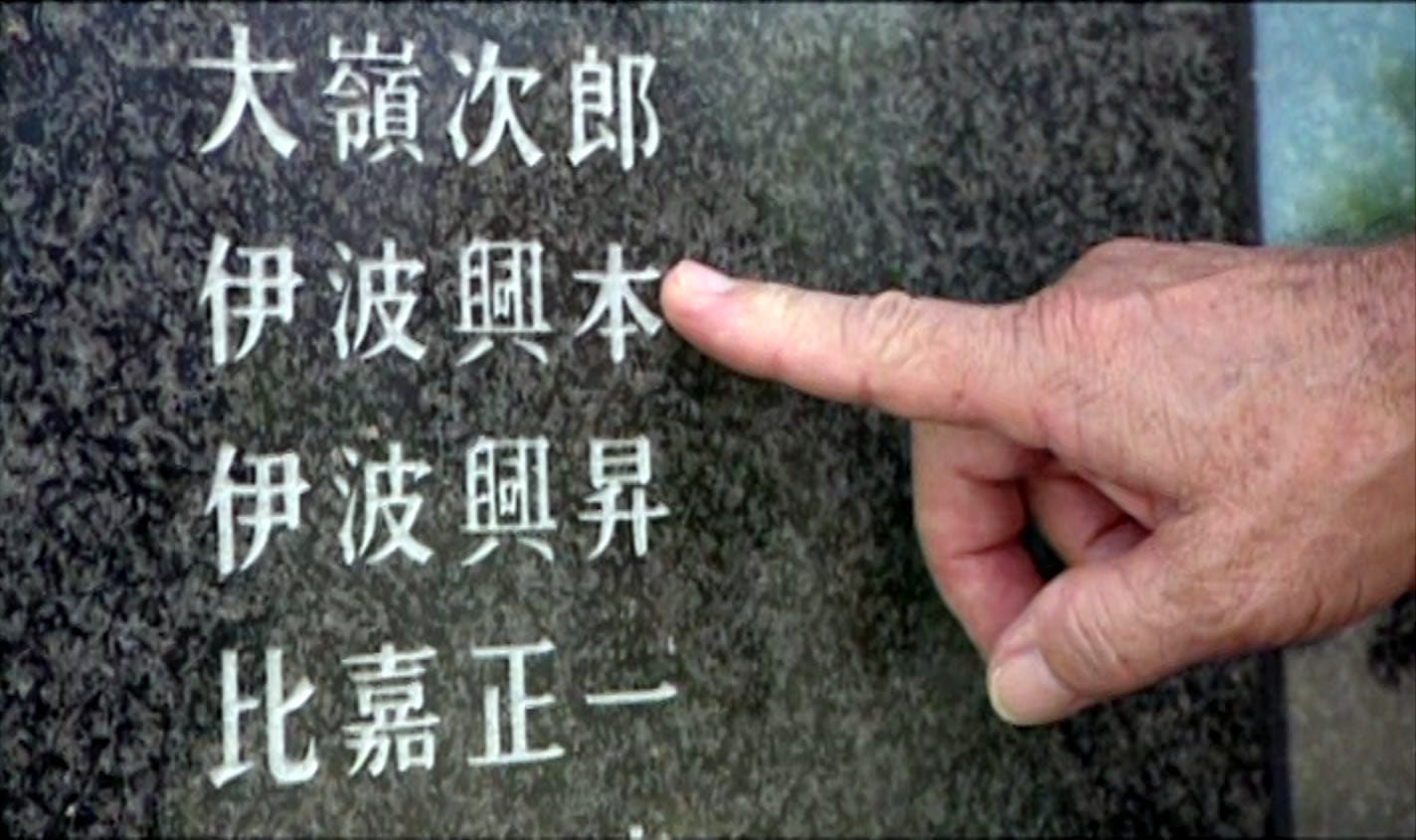

Deadly Arts: Karate is an episode in a documentary series by Canadian filmmaker, Josée Normandeau. It was shot on Okinawa. Several karate sensei are featured, including the late Iha Koshin 伊波庫進 (1922-2012). At one point, Normandeau takes Iha Sensei to the Okinawa Prefectural Peace Park. There, for only the second time, he views the Cornerstone of Peace, a monument to those who died in the massive Battle of Okinawa in 1945. Echoing the Vietnam Veterans Memorial in Washington, the names of the dead are inscribed across its many stone walls. There is however, a crucial difference: if you visit there, you will see the names of not only the soldiers of one nation, but those of everyone who died in that terrible battle, whether Japanese, American, Okinawan, or a citizen of any other country, whether military or civilian. There are over 240,000 names and more are added each year with the discovery of casualties not known before. More than a third of the population of the island was killed.

Among those memorialized are Iha Sensei’s father and brother. When Normandeau asked him how he felt when he saw their names, he replied, “My sorrow is no more important than anyone else’s whose loved ones’ names are written here.”

His words struck me deeply, and they resonate even more now that he is gone. In their simple modesty, they articulate the essence and difference of the way of karate. The death of someone you love is such a singular and personal event, like nothing else in life. Yet even in the return and consideration of that extremity, what Iha Sensei offered was not his own private grief, no matter how profound that was, but rather how that grief was shared. He knew he held it in common with all the survivors of the Battle of Okinawa. There is the paradoxical crux of the matter: what is experienced or possessed by everyone defines the ordinary. What is common is mundane. But Iha Sensei recognized that sometimes it is the very mundanity of something—the fact that it is shared by a collective or a community—which makes it special. The ordinary can be extraordinary because it is ordinary.

The pertinence to karate-dō is manifold. I once saw a newscast about a deadly attack in the Middle East. The mother of one of those killed wept on the screen and, in her grief, cried out that those of the other side were animals who did not feel the pain that she did. I felt deeply for that bereft mother. As a father, I can imagine nothing worse than losing a child. But the contrast with Iha Sensei was stark. She thought her grief elevated her above her enemies, because she was sure that they did not share the love and hurt that tore at her soul. She did not even think they could be human.

But of course, they were human, and of course they loved and hurt. Those on both sides of every awful conflict have. That is why the Cornerstone of Peace lists the names of all the dead, whatever their provenance. The loss and grief of everyone matters. There is a fundamental obligation to honour that commonality and not hold our own love and pain as higher or more tragic than anyone else’s. The ordinariness of loving and losing the ones we love is a simple and universal burden of having a heart. And that is truly extraordinary

One of the guiding tenets of karate-dō is to seek to understand how lessons of death teach us about life. Then what import can Iha Sensei’s words have for our daily lives? In the manner of Asian teaching fables, the answer is given in the question itself, for it teaches us the specialness of our ordinariness.

When we practice karate, it’s important that we envision a life-and-death battle, so that there is urgency, seriousness, and realism in our technique. Training is always preparation for the potential time when we have to defend ourselves or our loved ones from a violent attack. Yet while that is true, it is also misleading, or at least insufficient. It’s true that karate that doesn’t work in fighting is useless, and your karate won’t work unless you train consistently, day after day, week after week, month after month, year after year. Karate is the opposite of diets that promise easy results in a couple of weeks. It takes a great deal of training and effort to be able to fight well. Yet this focus on self-defence frames endless practice as the mundane preparation for the real thing, for what is important or special.

From that perspective, a karateka in the dojo is like a football player on the practice field or a musician in the rehearsal hall. The thing that really counts is the fight, the game, or the performance. This is a good characterisation of sport karate, where you practice to succeed at what matters: winning a match or a tournament. Practice is then the means to an end, the ordinary, repetitive thing that is the prerequisite for the extraordinary occasion.

However, this straightforward notion of practice is predicated on its opposite. It’s well-established that karate, like all effective combative methods, is only functional if it’s practiced so often and intensely that its techniques become natural, if they become thoroughly part of who you are, so your body can act and react much faster and more efficiently than if you had to think about what to do. In other words, practice is a transformation of the self. Training makes you a better fighter by making you faster, stronger, calmer, tougher, more skillful, more supple, more aware, more disciplined, more relaxed, and less fearful or full of doubt.

Still, serious karate practitioners are obliged to take one step further: they must recognize that this many-sided transformation is not the just means to the end of becoming a good fighter, but also and more importantly the end itself. The significance of combat to karate is less the possibility of a street fight than it is the certainty that principles of martial traditions structure the ethos of practice. So, the key is an inversion: you don’t train to fight—even though training does develop the capacity to fight—fighting teaches you how to train, and, thereby, how to make yourself a better human being.

To return to the original point, how does this apply to the ordinary and the extraordinary? The answer stems from a Japanese proverb, narai sei to naru 習い性となる: “practice becomes one’s nature.” Or, “you become what you do.” More specifically, you become what you do over and over; you become what you do every day. It’s that simple and that difficult, especially in these times. If you are going to succeed in karate, practice has to be the most ordinary thing in the world. It has to become like eating or sleeping or breathing, something that is a necessary, repetitive part of existence. You need to work the extraordinary circumstances of life-and-death battle as ordinary daily practice. Karate becomes extraordinary precisely when it becomes ordinary, because then karate becomes what you are.

It is days after my first reading and I am still processing this work. Although I appreciate the ideas, a part of me resists. The terms ordinary and extraordinary demand a rigid dominance heirarchy, refusing the fluidity of these interpretations. This says something significant to me about the hold language can have over us, and how fighting this is perhaps a reflection of training. I think I will need to revisit this piece, like a kata, to absorb it more fully.