Between Openness and Stubbornness

How to persist when your teaching succeeds and fails

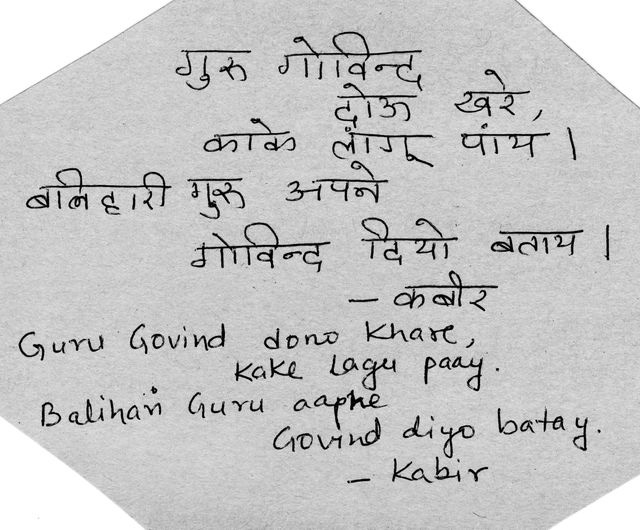

A few years ago, student of mine left to return to India. She gave me a card on which she had copied, in her beautiful Hindi hand, a verse about teaching by Kabir Das. I was and remain very ignorant of Indian literature, so I was grateful to be introduced to him. Her card is now a treasured possession.

This isn’t meant to be a variant of the humble-brag, using the appreciation of a student as transparent cover for self-congratulation. Instead, the necessary context is that I was, at the same time, dealing with a message from another student that was an eruption of complaints and invective.

The point isn’t to paint the first as a good student and the latter as a bad one, nor that I might use what the first said as a defense against the other. It’s not about redemption or reassurance, no matter how much part of me craves both.

Instead, it’s about how someone persists as a teacher when their teaching fails. Teaching is not something a teacher does—it’s always relational, always dependent on both teacher and student and lived out in the particular dynamic between them. But blaming a student for a failure of teaching, regardless of what they did or did not do, is always a cop-out. A teacher is always responsible; they could have always been different or better, even though the same applies to the student.

To me, the responsibility of the teacher is adjudicated in the tension between openness and stubbornness. I take it as a given that every good teacher remains a student of teaching, striving (although not always successfully) to be open to different ideas, techniques, approaches, conceptualizations, and therefore open to changing as a teacher, even radically so. But that openness is paired with what the Japanese call ganko 頑固, an obstinacy that borders on pig-headedness. In Japan, there is a particular esteem for the craftsperson, whether it’s someone who dyes cloth, creates ceramics, or makes sushi. There’s a recognition that if the shokunin 職人—the craftsperson—is truly serious about their craft, then in their hands, it must be shaped by their individual, personal vision and commitment. Not someone else’s, and certainly not the consensus of a group.

As many have recognized, teaching is a craft. Teaching karate certainly is. My responsibility as a teacher is to always strive to be a better one. In the Japanese mind, ganko is the direct consequence of refusing to settle for less than that responsibility. The craftsperson is stubborn because they refuse to compromise, not because they narcissistically think they are above criticism, but because they will not moderate their endless quest to be better for the sake of popular endorsement or accommodation of a particular dissatisfaction.

As a teacher of karate, the parallel is the vast multitude of extant fighting disciplines. I am stubbornly allegiant to karate, not because I think that karate is “better” than MMA or BJJ or kung-fu, but because I am committed to its way, to keep working towards being the best practitioner and teacher of it I can, despite my egregious faults and limitations.

So when I am noisily rejected by a student, I take a little while to lick my wounds, then put on my keikogi (practice uniform) again and put my feet back on the way, this time keeping the exalted company of Kabir Das.

Never give up.

"I take it as a given that every good teacher remains a student of teaching, striving (although not always successfully) to be open to different ideas, techniques, approaches, conceptualizations, and therefore open to changing as a teacher, even radically so."

Teaching is learning and requires many skills: Humility and strength, patience and drive. Understanding and empathy but also determination to bring about change; respect for the student's current position in their life while also demonstrating a strong desire for them to keep growing and become the vision we and they desire for themselves. Wisdom and education are both outside and inside of the student :D

What a tough profession that I wouldn't have any other way.

I was told once that the First Nations (and I couldn't tell you specifically which group) on BC's west coast use the analogy of a sharp double-edged sword to represent life and it's decisions that can cut both the holder and the recipient.

What a very fine balance! And I'm glad I read this blog post on my first day back. It gives me the strength to continue honing my craft. Thank you.

"...the tension between openness and stubbornness..." captures this place perfectly. Thank you Sensei!